If you prefer to buy tickets over the phone, please call: 704.372.1000

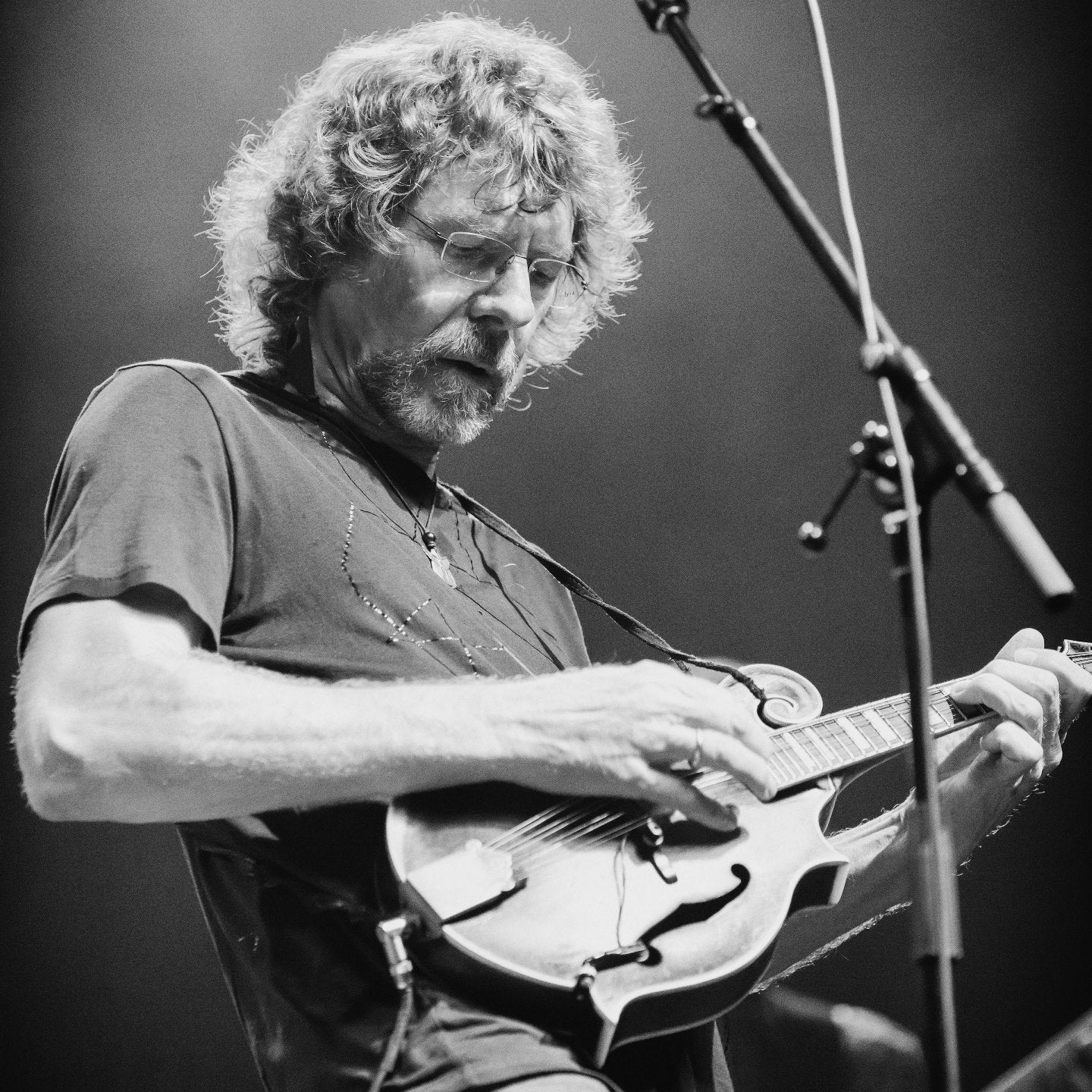

Sam Bush

Opener: Western Centuries

Oct 4, 2019 • McGlohon Theater

-

Pricing:$29.50 - $42.40

-

Presented by:

Overview

There was only one prize-winning teenager carrying stones big enough to say thanks, but no thanks to Roy Acuff. Only one son of Kentucky finding a light of inspiration from Bill Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys and catching a fire from Bob Marley and The Wailers. Only one progressive hippie allying with like-minded conspirators, rolling out the New Grass revolution, and then leaving the genre's torch-bearing band behind as it reached its commercial peak.

There is only one consensus pick of peers and predecessors, of the traditionalists, the rebels, and the next gen devotees. Music's ultimate inside outsider. Or is it outside insider? There is only one Sam Bush.

On a Bowling Green, Kentucky cattle farm in the post-war 1950s, Bush grew up an only son, and with four sisters. His love of music came immediately, encouraged by his parents' record collection and, particularly, by his father Charlie, a fiddler, who organized local jams. Charlie envisioned his son someday a staff fiddler at the Grand Ole Opry, but a clear day's signal from Nashville brought to Bush's television screen a tow-headed boy named Ricky Skaggs playing mandolin with Flatt and Scruggs, and an epiphany for Bush. At 11, he purchased his first mandolin.

As a teen fiddler Bush was a three-time national champion in the junior division of the National Oldtime Fiddler's Contest. He recorded an instrumental album, Poor Richard's Almanac as a high school senior and in the spring of 1970 attended the Fiddlers Convention in Union Grove, NC. There he heard the New Deal String Band, taking notice of their rock-inspired brand of progressive bluegrass.

Acuff offered him a spot in his band. Bush politely turned down the country titan. It was not the music he wanted to play. He admired the grace of Flatt & Scruggs, loved Bill Monroe- even saw him perform at the Ryman- but he'd discovered electrified alternatives to tradition in the Osborne Brothers and manifest destiny in The Dillards.

See the photo of a fresh-faced Sam Bush in his shiny blue high school graduation gown, circa 1970. Tufts of blonde hair breaking free of the borders of his squared cap, Bush is smiling, flanked by his proud parents. The next day he was gone, bound for Los Angeles. He got as far as his nerve would take him- Las Vegas- then doubled back to Bowling Green.

"I started working at the Holiday Inn as a busboy," Bush recalls. "Ebo Walker and Lonnie Peerce came in one night asking if I wanted to come to Louisville and play five nights a week with the Bluegrass Alliance. That was a big, ol' 'Hell yes, let's go.'"

Bush played guitar in the group, then began playing after recruiting guitarist Tony Rice to the fold. Following a fallout with Peerce in 1971, Bush and his Alliance mates- Walker, Courtney Johnson, and Curtis Burch- formed the New Grass Revival, issuing the band's debut, New Grass Revival. Walker left soon after, replaced temporarily by Butch Robins, with the quartet solidifying around the arrival of bassist John Cowan.

"There were already people that had deviated from Bill Monroe's style of bluegrass," Bush explains. "If anything, we were reviving a newgrass style that had already been started. Our kind of music tended to come from the idea of long jams and rock-&-roll songs."

Shunned by some traditionalists, New Grass Revival played bluegrass fests slotted in late-night sets for the "long-hairs and hippies." Quickly becoming a favorite of rock audiences, they garnered the attention of Leon Russell, one of the era's most popular artists. Russell hired New Grass as his supporting act on a massive tour in 1973 that put the band nightly in front of tens of thousands.

At tour's end, it was back to headlining six nights a week at an Indiana pizza joint. But, they were resilient, grinding it out on the road. And in 1975 the Revival first played Telluride, Colorado, forming a connection with the region and its fans that has prospered for 45 years.

Bush was the newgrass commando, incorporating a variety of genres into the repertoire. He discovered a sibling similarity with the reggae rhythms of Marley and The Wailers, and, accordingly, developed an ear-turning original style of mandolin playing. The group issued five albums in their first seven years, and in 1979 became Russell's backing band. By 1981, Johnson and Burch left the group, replaced by banjoist Bela Fleck and guitarist Pat Flynn.

A three-record contract with Capitol Records and a conscious turn to the country market took the Revival to new commercial heights. Bush survived a life-threatening bout with cancer, and returned to the group that'd become more popular than ever. They released chart-climbing singles, made videos, earned Grammy nominations, and, at their zenith, called it quits.

"We were on the verge of getting bigger," recalls Bush. "Or maybe we'd gone as far as we could. I'd spent 18 years in a four-piece partnership. I needed a break. But, I appreciated the 18 years we had."

Bush worked the next five years with Emmylou Harris' Nash Ramblers, then a stint with Lyle Lovett. He took home three-straight IBMA Mandolin Player of the Year awards, 1990-92, (and a fourth in 2007). In 1995 he reunited with Fleck, now a burgeoning superstar, and toured with the Flecktones, reigniting his penchant for improvisation. Then, finally, after a quarter-century of making music with New Grass Revival and collaborating with other bands, Sam Bush went solo.

He's released seven albums and a live DVD over the past two decades. In 2009, the Americana Music Association awarded Bush the Lifetime Achievement Award for Instrumentalist. Punch Brothers, Steep Canyon Rangers, and Greensky Bluegrass are just a few present-day bluegrass vanguards among so many musicians he's influenced. His performances are annual highlights of the festival circuit, with Bush's joyous perennial appearances at the town's famed bluegrass fest earning him the title, "King of Telluride."

"With this band I have now I am free to try anything. Looking back at the last 50 years of playing newgrass, with the elements of jazz improvisation and rock-&-roll, jamming, playing with New Grass Revival, Leon, and Emmylou; it's a culmination of all of that," says Bush. "I can unapologetically stand onstage and feel I'm representing those songs well."

Western Centuries Bio:

When did country music start to sound the same? The first generation of country artists borrowed from everything around them: Appalachian stringband music, Texas fiddle traditions, cowboy songs, Delta blues. In an era of unprecedented access to our musical pasts, shouldn't country music be even more diverse than it was in its infancy? Honky-tonk supergroup Western Centuries, back with a new album in 2018, surely understands this. They aren't bound by any dictum to write songs in a modern country, or even a retro country style; instead they're taking their own personal influences as three very different songwriters and fusing it into a sound that moves beyond the constraints of country. Part of the reason they can make music with this range of influences is because of their roots in city life. Both Cahalen Morrison and Ethan Lawton, two of the three principal songwriters, live in Seattle's diverse South end, and the third songwriter, Jim Miller, spends most of his time in and around New York City. The urban landscape is rarely mentioned in country music, but it makes for a refreshing sound that draws as easily from modern R&B as it does George Jones. It helps too that the album was recorded and co-produced by acclaimed musician and Grammy-winning producer Joel Savoy in Eunice, Louisiana, where local Cajun and Creole artists have always been adept at marrying old country sounds with R&B and rock n roll.

With Songs from the Deluge, out in 2018 on Free Dirt Records, Western Centuries brings three songwriting voices together into a more unified sound than ever before. Over the past year of heavy touring (since the release of their last album), they've pushed each other hard as songwriters. But with a band this well tested on the road, it's the sonic and lyrical places where each artist's styles depart that's most interesting.

Ethan Lawton, known for his earlier work in Zoe Muth and the Lost High Rollers, loves to pen imaginative parables about people living at extremes. "Wild You Run" by Lawton tells the story of watching someone you love deteriorate with a crippling addiction. The subject chases his temptation, but loses his soul as Lawton cries out helplessly "I won't tell mama what you done, go have your fun....” Lawton's "My Own Private Honky Tonk" is a rambunctious new take on the drinkin' alone narrative which finds Lawton dancing and playing music until the downstairs neighbors call. It's a boogie-woogie flavored tune à la Fats Domino that highlights the upright bass work of Nokosee Fields, the band's newest member. With the opening track, "Far From Home,” Lawton wails "mother, dear mother, won't you spin a yarn about the way things were.” It's about the dark days that young men found abroad in Vietnam and the personal wars they had to fight when they returned back home.

Cahalen Morrison, known for his earlier duo work with Eli West, is the country boy to Lawton's urban cowboy, inspired by his love for cowboy poetry and the New Mexican desert where he grew up. He's got a knack for bending words around stories until they're as funny as they are tragic, as fantastic as they are real. His songs grow like mesquite in the desert; they twist and turn. On "Earthly Justice," Morrison sings of barflys and their troubles, remarking sardonically "if earthly justice just don't get them in the end, there's always a heavenly trial on its way" as vocal harmonies and pedal steel two step all around him. On Morrison's album closer "Warm Guns,” he waxes quixotic about loss in love, singing in Spanish about being a victim of his own flaws.

Jim Miller, known for his earlier work with Donna the Buffalo, is the resident psychedelic poet. Like the best country songwriters, Miller's sense of communion with nature turns his songs into works of magical realism. On "Wild Birds", a song about a road-bound band, he consults the moss, befriends the tide, and survives fire all while asking for prayers to guide his band home to the end of their migration. "Borrow Time" features Louisiana accordion legend Roddie Romero, and the album's best harmonies between the three lead singers. Some of his most beautiful lines happen on "Time Does The Rest" as he sings "Your heart knows what's best / Hold her close, the lips will confess / Let it rise let it fall, time does the rest".

Western Centuries' music crosses vastly differing geographies, the city, the southwest, the metaphysical. And their musical influences are equally as diverse. Together, they weave a tapestry of western music, without sacrificing their hard-earned country dancehall sound. Songs from the Deluge will levitate heavy hearts, turn spilled beer into ballads, and bring country music home as literate, epic odysseys from parts unknown.

Event Showings

Click the calendar icon below to add the event to your calendar.

This event has already occured.